Project

School governor 1988 – 1998

In 1992 I attended a meeting at the House of Commons to raise awareness of the need to encourage more Black parents to become school governors.

I became a school governor at George Dixon J&I School, Birmingham, in 1988 when my two youngest children were pupils there. One of the things that motivated me most was the underachievement of black children, especially boys, in the education system.

Reports on this issue had highlighted the lack of culturally relevant books and educational materials in the curriculum, the absence of black teachers, and low expectations from staff as possible factors. I felt that with my experience from working in education and developing and publishing books, I could make a valuable contribution to the governing body.

I was also aware that many black parents were unhappy at the way they perceived black achievement was either ignored or marginalised at the school. Many felt, and I agreed with them, that the school should be teaching the children about black role models and black achievement to help foster in African Caribbean children a positive self image and to counter the negative stereotypes sometimes held by other sections of society.

In short, we wanted our children to be going to a school where the environment – from the books in use, pictures on walls, to events and learning activities – reflected all the cultures in the school, so that all the children could learn about each other’s cultures in a positive way.

I voiced these concerns at governors’ meetings and pointed out that there was no celebratory event in the school calendar that black children could identify with or claim to be theirs. Inevitably, the absence of African Caribbean images in the school became more vivid at times of religious or other special assemblies and festivals, such as Divali, Eid or Chinese New Year, which the school had embraced.

Things really came to a head when it was announced that further assemblies would be held to celebrate the birthday of Guru Nanak and the centenary of Nehru’s birth. Whilst no one doubted the legitimacy of these celebrations – especially in a school where 70 per cent of the pupils came from Asian backgrounds – it nevertheless drew even more attention to the lack of similar events reflecting black experiences.

Martin Luther King Jnr birthday celebration

In order to head off a potentially explosive confrontation between some of the more vocal black mothers and the school, I suggested to the head, Hugh Heaven, that the school might add Martin Luther King Jnr’s birthday celebration to the calendar. He agreed immediately and sent out a letter to parents the following day announcing that the school would mark Dr King’s birthday on January 15 with a special assembly.

I think it’s important to realise that many teachers were unsure of how to approach some of these issues back then – it was really a case of coming up with suggestions that they could work with. The choice of Martin Luther King was topical because although America had considered making his birthday a national holiday since the late 1970s, it was only after Stevie Wonder’s single ‘Happy Birthday’ (released in 1980) had revived interest, with more than six million people signing a petition to Congress, that President Reagan finally signed a bill into law. The holiday was first observed in the US in January 1986.

In addition, Mr Heaven suggested that Shrove Tuesday could be celebrated with a Caribbean carnival theme. I thought this was a very positive step because although most of the black children at the school came from Christian backgrounds – and therefore, it was argued, their religious festivals were observed as a matter of course – this was the first time that the school would recognise the unique ways black communities celebrate these special days.

So, on the 15th January 1990, a special assembly was held to celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday, with parents and friends invited. Oscar Stewart from Birmingham multi-cultural support services conducted a very enjoyable, interesting and inspiring assembly that brought the work of Dr King and the civil rights movement vividly to life. The event attracted the attention of a local photojournalist, Kevin Small, and a small story with a photograph appeared in the UK edition of The Jamaica Gleaner.

Topic work around the life of Martin Luther King was undertaken by all the children afterwards, and teachers reported on the high interest level – especially from the young black boys. Some of the many interesting pieces of writing and drawings produced were displayed in the classrooms, along corridors and in the halls.

The positive feelings that this initiative produced opened a way for more dialogue with the school. I co-ordinated some parent meetings and we decided to propose a conference to bring teaching staff and parents together to discuss how we could build on the Dr King initiative.

I called a meeting with parents to discuss this, and, overwhelmingly, mothers wanted to talk about how to improve the education of their children. We decided to call for a conference, with invited black educationalists giving short talks about education and the black child, with parents and teachers taking part in workshops.

Parents were full of enthusiasm for the event, and everyone volunteered to contribute towards organizing the day’s activity, including catering, crèche, publicity, contacting speakers, etc. The Head, Mr Heaven, welcomed the conference and agreed to attend with other teacher representatives.

Through the school liaison officer, Mrs Virmal Dodd, we were informed of the possibility of obtaining a £200 grant from the Birmingham City Council Women’s Festival to fund the conference. We quickly contacted potential speakers, put an application together and succeeded in securing the grant.

Our first choice of venue for the conference, naturally, was to hold it in the GD Junior and Infant building, but there was insufficient space for a conference, workshops and a crèche. We were, therefore, very grateful for the accommodation provided by the secondary school, who made all of their newly equipped crèche facilities available for the whole day.

Between the beginning of January and the day of the conference, March 21st, we held a number of meetings in ‘The Hut’ (a small outbuilding in the playground) at GD J & I, usually first thing in the morning after dropping the children off at school, to co-ordinate our activities

In the meantime, preparations went ahead for the Caribbean Carnival-themed Shrove Tuesday, where children, staff and parents celebrated with music, poetry, Caribbean songs and festivities, dressed up in stunningly beautiful costumes. Much credit went to the teaching staff who worked very hard, over a period of weeks, in the preparation and staging of the event. Books, posters and other educational materials which reflected African Caribbean culture and history were bought and added to the library.

The Conference, Education and the Black Community, was held on 20 March 1990. Together with Mrs Dodds, I put together a panel of black teachers and educationalists: Gilroy Brown, headteacher; Oscar Stewart, multicultural adviser; Narghis Rashid of the Governor Training Unit; Moira Foster Brown, headteacher; and Carlton Duncan, headteacher at George Dixon senior school.

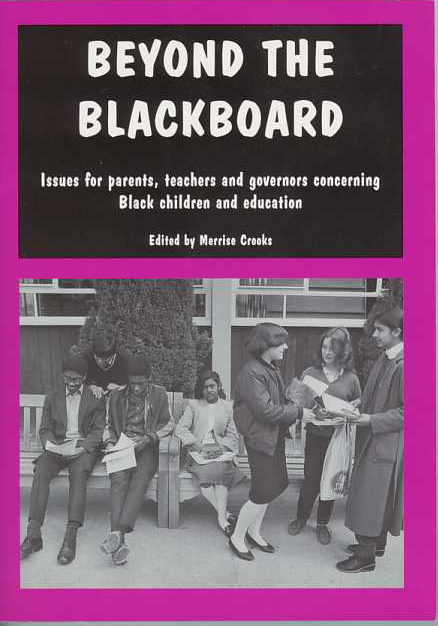

Beyond the Blackboard, a series of essays about eduction and the Black Community which came out of a conference I helped organise whilst I was a School Governor

Education and the Black Child Conference

The conference day was one of stimulating and informative speeches, lively group discussions, and an invaluable exchange of ideas and information.

Moira Foster-Brown from Wattville Nursery and Infant School talked about her school and the way it is organised to ensure that all cultures are represented.

Oscar Stewart from the Multi-Cultural Support Services talked to parents about their rights and the new Education Reform Act.

Gilroy Brown’s talk on the importance of creole in language development provided an understanding of the linkage between our African Caribbean heritage, our language, and the needs of the African Caribbean child. He emphasised the creative potential of creole languages such as Jamaican patois.

Carlton Duncan gave a talk on pastoral care, emphasising the need for a fuller understanding of the cultural needs of black children.

Narghis Rashid gave a talk on the role of governors in the new Education Reform Act, and training provision available.

The afternoon workshops provided the opportunity for exploratory discussions, and exchange of ideas and information on issues raised in the conference. I led one of the workshops on positive role models for black children and we resolved that:

- Parents should be encouraged to communicate with school;

- We would like to see more black teachers;

- More black governors;

- There should be education/training for parents – easier access to courses;

- The national curriculum needed to incorporate a black perspective.

Irma Ramos led a second looking at parent/teacher relationships which came up with the following resolutions:

- More two-way communication between school and home;

- Parents to ask to see the books – and study them;

- Teachers should accentuate the positive;

- Extend children as far as possible;

- Teachers-parent relationship should be a supportive one.

Representatives to the conference included parents and teachers from George Dixon Junior and Infant School, members of the Board of Governors, Birmingham City Council Women’s Unit, Social Services, and local churches.

It was clear from the response from the parents, teachers and others in education how important it was for all schools to address the issues raised by the conference. It was hoped that the conference would be the start of an ongoing debate.

Although the event arose out of local concerns, the issues raised were of national significance, and it was recognized that these topics would make an important contribution to a wider audience. As the Director of Handprint I suggested that we could possibly publish the proceedings from the conference. Eventually we agreed to launch the publication at the following year’s Women’s Festival, as both a fitting tribute to the hard work and resolution of the (mainly) women who had made the event possible. Handprint covered the cost of typesetting, editing and printing the book, which Derek designed.

Beyond the Blackboard was published during the Women’s Festival of 1991 and launched in Birmingham by the High Commissioner of Jamaica, the Hon Mrs. Ellen Gray Bogle. A photograph of the launch was published on the front page of the Jamaica Gleaner. The book was subsequently distributed widely in the UK.

Celebrating Dr King’s Birthday on the third Monday of January has now become part of the tradition at George Dixon Primary and Infant School and every year a special assembly is held and an important dignitary is invited to participate. These have included the Bishop of Birmingham, other religious and political figures together with parents, teachers and members of the community. On one occasion the children wrote a letter to then Prime Minister Tony Blair about their event, which was reported in the local press.

Of course, the mere fact of having a Martin Luther King celebration didn’t eradicate black underachievement at the school, nor solve all the problems associated with high spirited children. But it did bring the school and the community together into a really meaningful dialogue, it opened the eyes of many teachers to ways they could be more inclusive – a difficult task in a school with many varied ethnicities, cultures and backgrounds – and it did provide, and continues to provide, a focus for black achievement.

And by bringing together a panel of some of the pioneer figures in black education at the time we shattered many of the prejudices and reservations held by both white and Asian parents about the suitability of bringing black teachers into the school. The following year, the junior school appointed its first black teacher, Mrs Rose Kelly, who inspired children at George Dixon for more than 20 years.